|

|

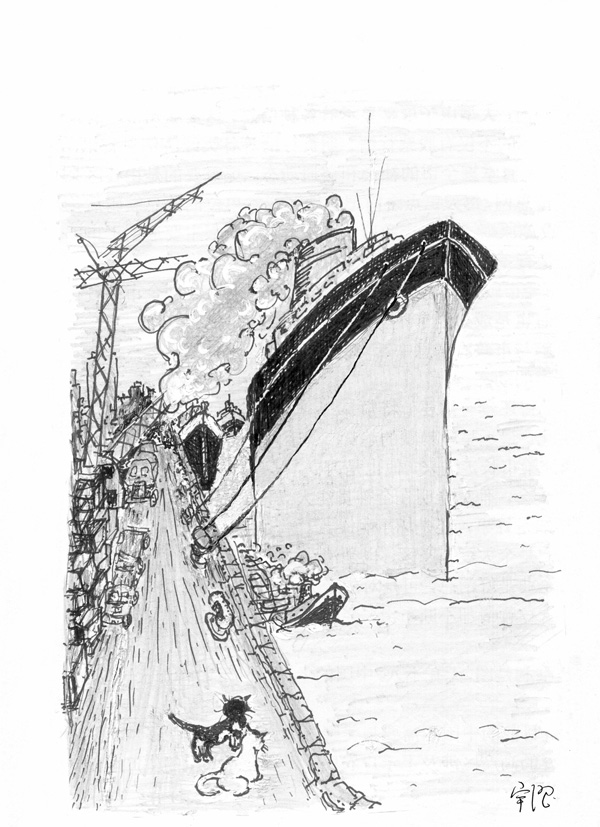

One of the illustrations Jin Yucheng sketched for Fan Hua depicts scenes of everyday life in old Shanghai. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

It was some of the first vignettes of downtown life that Jin wrote in the Shanghai dialect and had serialized online, that were later threaded together as the firsthand experiences of the main characters and developed into the final storyline.

Throughout the book, Jin refrained from describing the characters' inner thoughts. Instead, he relied on colloquial dialogue, embedded with local phrases and expressions, to help the readers discover the abundance of unspoken words and emotions on their own.

"Normally I allow context to convey the subtext," says Balcom, who is also a professor at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey in California.

He added that with a Shanghai dialect dictionary in hand and under the guidance of the author, he was able to translate the idioms and dialect for meaning.

However, thepaper.cn reports that the author hoped the translator would not concentrate too much on the Shanghai dialect and focus more on the spoken word of their own language.

Balcom has been studying Chinese for 40 years and has spent a few years in Shanghai, Beijing and Taipei. He says the novel resonated with him from his stay in Shanghai at the end of the 1980s, and that he is tempted to write a reader's guide to accompany the book.

And now that he has translated 20 out of the 31 chapters in nearly two years, Balcom hopes to finish the first draft by the end of August.

As a prestige publisher working with dozens of prizewinning authors, including the Nobel Prize, Pulitzer Prize and the US National Book Awards, FSG's involvement proved inspiring to other publishers.

Hayakawa Publishing, with the largest number of translated works of literature in Japan and which has published works of Nobel laureate Kazuo Ishiguro, followed in FSG's footsteps within a week.

Rika Uramoto, a professor at Osaka University of Economics, will undertake the Japanese translation of the book, and he has worked on other works by Jin. Uramoto speaks some Shanghainese and has friends who live in nearby Suzhou.

There has been a growing interest in translated Chinese literature in recent years.

The Guardian recently reported that translations of Chinese works are "in growing demand" in the United Kingdom, where Chinese sci-fi and fantasy novels such as Liu Cixin's The Three Body Problem and Louis Cha's Legends of the Condor Heroes: A Hero Born sell strongly.

A deal to translate Liu's Hugo Award-winning work into Japanese with Hayakawa was inked recently.

However, Peng says there is a lack of foreign rights agents in China who are familiar with common practices for translation deals and who also have connections with publishing circles overseas.

It turns out that Chinese authors are relatively quiet on the international publishing scene.

Peng, who has been dealing with foreign literature publishing in China for 15 years, resigned from his former company around two years ago and is now helping a dozen Chinese authors to publish their works abroad.

"They need help and I'm on my own now," he says.

Peng says that Wong's devotion to bring the novel to the big screen has been really helpful in reaching a deal with FSG.

Meanwhile, Peng and his translators continue to work mainly out of interest. It's hard to earn a living simply as a foreign rights agent, Peng says.