|

|

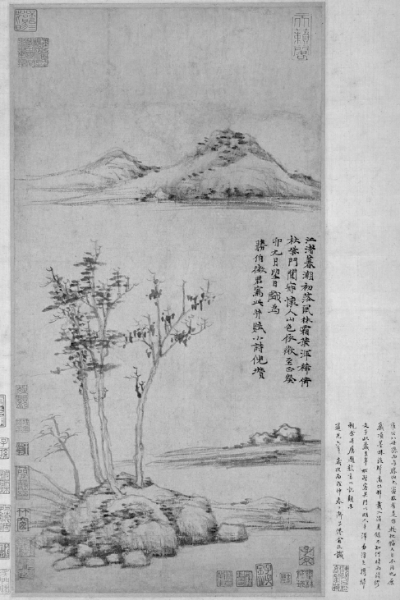

Wind among the Trees on the Riverbank, 1363 by Ni Zan, is on display at the exhibition Streams and Mountains without End: Landscape Traditions of China.[PHOTO BY GAO TIANPEI/CHINA DAILY] |

"I remember him saying: 'At last, a space big enough to hold my collection,'" Hearn says.

In the intervening years Hearn also learned Chinese, both modern and classical. However, the raw experience of looking at a wildly executed piece of ancient Chinese calligraphy, of feeling the strength of every stroke while not knowing what it exactly means, has stayed with him.

He tapped into that feeling as a curator, first with a 1970s show that juxtaposed calligraphic works from both in and outside of China, and then with an uncompromisingly contemporary one titled Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China, in 2014.

"Wen Fong is a great tennis player. He talked about calligraphy the same way you might talk about an athletic performance by Roger Federer. In both cases, it's about trying to liberate yourself while trusting your own hand at a certain amount-the combination of physical training, mental focus and spontaneity," he says, trying to explain the sense of thrill someone who is not Chinese might feel looking at a work of Chinese calligraphy.

"A skier navigating the courses down a mountain slope might go through the same kind of excitement a calligrapher experiences with his brush," Hearn says.

"Westerners who know about action painting, about gesture and speed, about figure-ground relationship, about positive and negative spaces can understand calligraphy, for all the elements are there," he says, linking the millennia-old art tradition with influential abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.