|

|

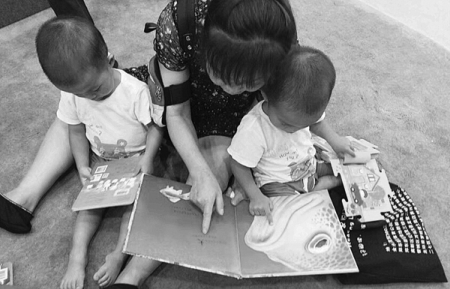

She reads for her grandchildren before her trip. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Driving a discussion

To make ends meet during her trip, she uploaded videos about her journey online, which have gone viral and contributed to a deep conversation about a woman's role in marriage.

Li Sipan, a woman's rights advocate in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, comments on Sina Weibo that many women share the same experience in their marriages, but Su is one of the few to have the guts to leave and talk frankly about her feelings.

"Su's story is the same as many women. Before marriage, she was the unfavored sister to her brothers. In marriage, her husband displays little concern about her as she looks after the home, their daughter and her grandchildren, ignoring her own needs," Li says, adding that even though she has a found a way out, it is, unfortunately, temporary, as she still has to return home at some point.

"As brave and independent as Su is, she cannot afford to divorce, which illustrate that a rethink about the current social system is required," Li adds.

According to China's traditional socio-cultural code, women are expected to stay in a marriage, no matter whether it is good or bad. There is an old Chinese saying, "If you marry a rooster, you stay with the rooster; if you marry a dog, you stay with the dog".

While it is a social contract consigned to the past, there are those in society that still cling to such beliefs. According to a report released by the National Bureau of Statistics in 2019, a married woman is expected to do most housework and take care of the elderly and children, even if she has a job. Chinese women on average spend more than 2 hours and 6 minutes a day on housework, compared with their male partners mere 45 minutes. In the average working day, women work 28 minutes less than men who work nearly eight hours every day.

It means that there is a clearly unequal division of labor, especially for working mothers, who shoulder more household responsibility than their partners, while sharing a similar financial burden.

For Ding Shiding, an author in Qingdao, Shandong province, women born after 1960, like Su, are different from the previous generation, most of whom saw their lives depend on husbands.

"Su is independent economically and psychologically," Ding says, adding that she has the freedom and can afford to explore the possibilities in life, which is kind of an improvement.

It is not only Su, though. An increasing number of women in China have challenged the traditional thinking on marriage, with men as the breadwinner and the social stigma of divorce. Chinese women were granted the right to divorce in 1950.

Zhou Qiang, the president of the Supreme People's Court told at a speech in Tsinghua University in November last year that nearly 74 percent of divorces in China are initiated by women.

Li Mingshun, a law professor at China Women's University, says amid the fast social development in China, people care more about the quality of their marriages.

In Western countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, women are reported to initiate divorce far more than men. In a 2015 study on US divorce cases, Michael Rosenfeld, an associate professor of sociology at Stanford University, wrote: "I think that marriage as an institution has been a little bit slow to catch up with expectations for gender equality."