|

|

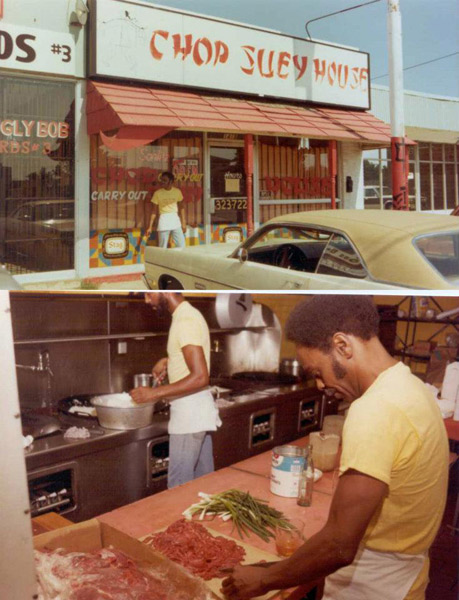

Adams outside his restaurant in Memphis; in the kitchen. [Photo provided by Della Adams to China Daily] |

Yet "low-key" could be hardly said of the press that had gathered for Clarence Adams at the Foreign Correspondents' Club, Hong Kong. He was bombarded with questions over a broadcast he had made the year before, through the Beijing office of the Vietnam National Liberation Front, to black Americans fighting the Vietnam War.

"You are supposedly fighting for the freedom of the Vietnamese, but what kind of freedom do you have at home, sitting at the back of the bus, being barred from restaurants, stores and certain neighborhoods, and being denied the right to vote?" he said in the broadcast.

Platt dealt with three "defector families" during his stay in Hong Kong, the other two being those of William White and Morris Wills, both of whom left the previous year. According to him, "these men returned home without fanfare and blended quietly into Mid-America", with the exception of Wills. Wills later wrote highly negatively about China, before he received a fellowship from Harvard and landed a job at Utica College in New York.

"Without fanfare"? Yes, if one does not count the relentless media hunting. "Blended"? No way. Calling the first few years in Memphis "the worst of my times", Della Adams was subjected to bullying "from the 3rd grade all the way to junior high" by her fellow students, most of them black.

"It never stopped," she said. "I got into at least one fight every week, because I looked different," said Adams, who at the time "always wore two pony-tails on the side of my head, trying to look as inconspicuous as possible".

"I didn't get hurt by racism from the white people until much later because I lived in a black neighborhood and went to a black school. Later I went to college and oh my God…"

|

|

Clarence Adams with his friends and fellow American POWs-turned-students in Beijing in the 1950s. [Photo provided by Della Adams to China Daily] |

The father, who understood that his daughter must toughen up, gave her a switchblade, with which she once successfully fended off a set of girls who "were going to hold me down and cut my hair".

"Be fearless-that's the most important lesson from my father, and it has carried me through my entire life," Adams said. "I watched as my parents crawled and clawed their way out of the most horrendous hardship."

Having received countless threatening phone calls, the family dared not leave the house for more than one week after they arrived in Memphis. During their first outing, "one white fellow" walked up to the father, called him a turncoat and spat at him.

Then there was the crushing poverty, something unknown to Della Adams growing up in the comfort of a "foreign-experts compound" in Beijing, with her father receiving three times what the average school teacher was paid.

The father, who had been given a dishonorable charge by the military, had great difficulty finding work, while the mother, who had made her husband probably "the only black man in Memphis or the entire state of Tennessee to have married outside his race", was later fired from her job sewing suitcases when this was found out.

"We had no money for food," Della Adams said.

Three weeks after their arrival in Memphis, Clarence Adams was subpoenaed in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee to defend, among other things, his decision to go to China. Instead of getting a lawyer to represent him, he chose to represent himself, with "unvarnished truth", to use his own words.

He recalled with bristling details how, in a deadly battle with the Chinese on Nov 29, 1950, he and his fellow black soldiers were left behind with their heavy artillery pieces and cumbersome transporting tractors-"sitting ducks for enemy mortar fire and machine guns"-while the light artillery regiment and the infantry unit, both comprised of white boys, had been ordered to retreat.

"Everyone knows that an artillery unit needs infantry to protect it …We did not stand a chance, and we got wiped out," Adams told the committee, whose members did not say a word for a long time.

Adams was later told to go home, yet his home phone was tapped for many years.

Things started to pick up for him in 1968 when two white brothers who ran a printing house employed him. Four years later the couple opened their "Chinese soul food" restaurant in Memphis, the Chop Suey House, chop suey being an American phonetic remake of the Chinese sha (chao) zasui, meaning fried mixtures of vegetables and meat.

An old picture shows the man at work, stir-frying what appears to be shredded onion in front of a big wok. Forever busy, he had no time either for writing his own memoir or joining his wife and daughter in their trip back to China in 1979, right after China and the US established formal diplomatic ties.

"We flew from San Francisco to Hong Kong, from where we took a train to Guangzhou, reversing our journey in1966," Della Adams said. "The moment I got off the train, I was on my knees, crying."

The couple eventually owned eight restaurants, one featuring a ping-pong table out back. "People came to play with the best player in Memphis," Della Adams said.

And the best player in Memphis was invited to play with the world's best players when the Chinese table tennis team made a 10-city tour of the US in the spring of 1972, reciprocating the US team's visit to China the previous year. Liu was also invited.

In the autumn of 2005, six years after Clarence Adams died, Wang the documentary director was in Memphis filming his interview with Liu and her daughter.

"She spoke to me as if she'd known me for a long time, in a totally unreserved and confident way," Wang said. "She told me that she wanted me to be with her the next time she visited China."

Liu died in 2007, aged 79, without ever again returning to China.

On that Friday night on Sept 17, 1999, Della Adams drove home alone after his father was pronounced dead by the hospital.

"I walked into the house. My mother was in her bedroom. She looked at me, then she took her small body, curled it up in a ball and screamed like she never did before.

"After my father was gone, my mother sold the restaurants. She also turned overnight into the opposite of her strong and decisive former self. Then I realize that they had been strong for each other."

In 2006 They Chose China premiered at the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was honored with a Golden Gate Award. When the lights lit up at the end of the movie, the director stood, turned around and saw "the sparkling in the eyes of the audience".

According to an American news report from the 1950s, the men in the movie were "the sorriest, most shifty-eyed and groveling bunch of chaps", about half of whom "were bound together more by homosexualism than Communism", the former being an even greater evil in mid-century America.

"To many, they are the unforgiven people of a forgotten war," Wang said, recalling his encounter on his flight to Los Angeles with an old US soldier in his late 70s, who insisted that the 21 were "traitors".

"To me they were idealists caught in the blinding spotlight of history before being thrown into its long shadow."

While in the POW camp, Clarence Adams wrote to a minister he knew back at the Memphis Metropolitan Baptist Church, asking him to pray for world peace. "I found out later he read my letter aloud to the congregation," he said.