Fried jiaozi served at Mama Lan's Restaurant in Brixton, south London is redolent with Beijing flavor. Photos Provided to China Daily

It is cold and bone-chilling weather, and the rising steam from cooking dumplings mist up the little shop. Ellie Buchdahl finds comfort in feasting on Chinese dumplings in south London.

In a corner of a marketplace, squeezed between stalls stacked with fruit and vegetables and brightly colored clothes, is a hole-in-the-wall restaurant. Diners wrapped in coats and scarves slurp steaming bowls of noodles and dunk crisp, lightly-fried jiaozi into little dipping dishes of vinegar and chili.

Some diners eke out a place at an outside table among jostling shoppers. One or two have found a space at the bar inside, where a small woman dressed in a plastic apron stirs huge bowls of woodear mushrooms, carrot and Chinese cabbage, while her daughter flicks, folds and stuffs the filling into dumplings.

The air is full of the juicy, salty smell of the Beijing market. Except Mama Lan's restaurant isn't in Beijing. It's in Brixton, south London.

Almost every British town has its Chinese takeaway or "oriental" restaurant, but it's unusual to find a place like Mama Lan's that takes you north of the Anglo-Cantonese menus with their wonton soups and prawn toasts.

Mama Lan herself (she goes by her family nickname) was born in Beijing.

Although she has been in the United Kingdom for 20 years, cooking what her daughter Ning Ma refers to as "the usual Cantonese-type stuff", she grew up cooking the most Beijing of Beijing foods.

She helped her father run his dumpling stand at a market near Jianguomen and waitressed at a nearby Muslim restaurant. She moved to Britain in 1992 when her husband, a head chef at Quanjude, was sent to work in a fledgling overseas branch of the famous Beijing restaurant in Manchester - a venture that never quite took off.

It was these northern flavors - the hearty soups, the meaty stir-fries and more than anything the dumplings - that were central to Ning's childhood.

Even after she and her parents came to Britain when she was 15 and Ning went to English school, became an accountant and started work in private equity house Coller Capital, she couldn't get those flavors out of her mind.

So Ning decided to take her mother's talent - and her own taste for Beijing food - to the British market.

"I was always cooking with my mum and talking about the old days," she says. "I had wanted to do something for ages, something that showed people there's so much more to Chinese food than what you get in the UK.

"So one day I just decided I'd had enough, and I gave in my notice at work and was like, right - I'm going to find a shop!"

Back in 1992, Ning says, Britain wasn't ready for a new kind of Chinese food "because people didn't travel as much and they didn't really get the whole theater behind things like roast duck".

But after a successful test run with the "Mama Lan supper club" in February 2010, she says she decided things had changed.

"We advertised on a central supper club website and people came to our house to eat and just paid a donation to the costs," she explains. "We did the first one to celebrate Chinese New Year and we were surprised how well people reacted to it. Suddenly we had loads of bookings and people were coming back again and again.

"We always made food at the supper club we would eat at home - dumplings, noodles, buns, that kind of thing. So when I started the restaurant, I just decided to do what we eat at home again - especially dumplings, because we love them so much!"

London proved to have the perfect location for a Beijing-style food stall.

Brixton in south London was once synonymous with gun crime, riots and drugs, but heavy investment in the early 2000s has transformed it. In 2009 developers took over a run-down 1930s shopping arcade and rebranded it Brixton Village, a covered market full of bakeries, boutiques and cafes. All the shops, from the Thai restaurant to the Pakistani snack stall, are carefully chosen to reflect the vibrant multicultural community of south London.

Ning pitched her Beijing restaurant in January 2011 and the managers jumped at it.

"They really liked the fact that we had a history and would bring something new to the market," she says. "I guess we were really lucky!

"Brixton Village reminded me of a Chinese market, like where my granddad and my mum had their shop," Ning continues.

"Usually in the UK, a fruit market is a fruit market and a veg market is a veg market, but in China people will be selling everything. In Brixton Village you'll have a greengrocer, then a butcher, then next to it a burger bar. It's really vibrant, just like Beijing. And it's more relaxed than in a restaurant - you just sit outside or get takeaway."

The idea had been simple - Ning would manage the business while her mother made the dumplings. But from the day they opened in October 2011, it was clear they had underestimated Brixton's taste for jiaozi.

"We actually ran out of food on that first day!" Ning laughs. "There were so many people wanting to be fed."

Now a handful of part-time helpers (almost none of them Chinese) helps in the tiny kitchen. There is no gas supply, but they manage with an induction cooker and hob, a couple of electric fryers and a few sinks run off two water heaters.

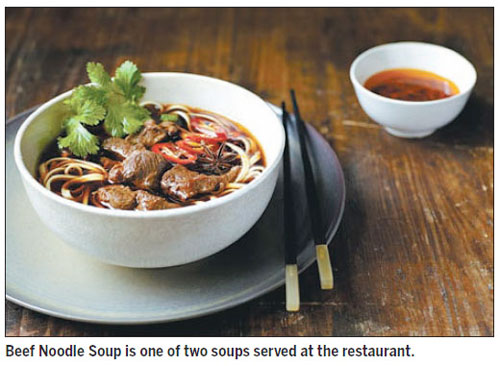

The menu is small and select. There are two soups, beef noodle and tofu; four kinds of jiaozi, including the Beijing classics of beef and spring onion, pork and Chinese greens, vegetable and king prawn; a handful of side dishes and a drinks menu of tea and, of course, Tsingtao beer.

The prices are admittedly higher than a true Beijing food stall - five jiaozi costing between 4.5 and 6 pounds ($7.2-9.6).

The timing isn't exactly Beijing-style either.

"We have to try to bring out all the food at the same time," Ning says.

"In China, you just get stuff as it's made, but we actually had some complaints online about that at the beginning, people saying the food is great but I don't fancy waiting around for my meal while my friend eats hers."

Ning knows Mama Lan's London restaurant can never be Beijing enough for Mama Lan herself.

"My mum misses her family more than anything," Ning says. "I think one day she'll go back for good."

But Ning plans to stay. "To be honest, I don't know how business works in China," she admits.

"And I love what I'm doing here. When you get things right and people are happy, it's a really nice feeling that you've made someone's day."

And she makes sure she gets her regular boost of home. "Beijing is a great city," Ning says. "I make sure I go back at least once a year for a feeding frenzy with my family!"

Contact the writer at sundayed@chinadaily.com.cn.

By Ellie Buchdahl