Chinese architecture constitutes the only

system based mainly on wooden structures of unique charming appearance. This

differs from all other architectural systems in the world which are based mainly

on brick and stone structures.

There are four

extant wooden structures of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), all of them being Buddhist halls

in Shanxi. They are very valuable; especially important are the two big halls --

Nanchan Temple and Foguang Temple.

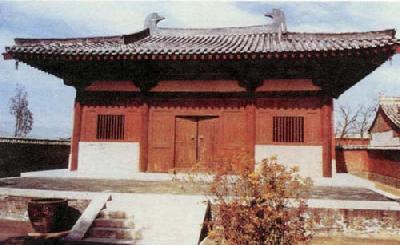

Located in the southwest of Wutai

Mountains, the Nanchan Temple, built in the 3rd year (782) during the reign of

Tang Emperor Jianzhong, is a very small hall, its plane close to a square shape.

Because it is in great depth, the roof is of a single-eaved Xieshan type

(two slopes on the upper part and four slopes on the lower). The slope of the

hall is very gentle. Because the plane is close to a square, if the Chinese

hipped roof (four slopes on the lower part) is adopted, the front ridge will

appear to be too short, and the structure will be very complicated. If

Xieshan is adopted, the proportions will be very suitable. Later, this

became the method generally adopted for halls of a square or close to a square

plane.

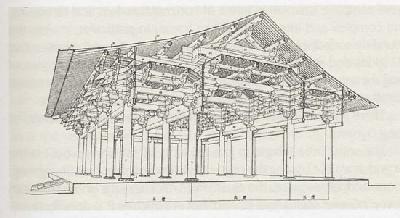

Located in Doucun Village at the foot of

Wutai Mountains, the Foguang Temple, founded in the 11th year (857) of Tang

Emperor Dazhong, is a medium-sized hall standing on the terrace at the back of

the temple.

The plane of the big hall is of rectangular

shape. It consists of seven rooms in the front, with a circle of inner pillars

within the hall dividing it into the heart and the surrounding two parts. In the

heart is a Buddhist altar on which there are five groups of statues in tacit

coordination with buildings. The roof is single-eaved Wudian, the slope

of the house is also gentle.

The composition

of the space represents a major characteristic distinguishing architectural

art from other plastic arts. The hall of Foguang Temple provides us with the only

important example for understanding the internal space of Tang Dynasty

structures. The core space is fairly high. The walls and Buddhist altar between

pillars also give prominence to its important position. Around the check-shaped

ceilings are slanting rafters, under which are thoroughly exposed beam frames.

These beam frames are both necessary structural members and an important means

of expressing the structural beauty and dividing the space. Between the wooden

structural members of the beam is vacuum .The space between makes "circulation"

possible, which is empty, bright and permeable. The grandiose beam frame and the

dense checks of the ceilings form the contrast between the coarse and the fine,

and the sense of weight. The low and narrow peripheral space serves as a foil to

the center space. But the designing methods for the beam frame and the ceiling

are identical. The entirety is accomplished at one stretch giving a strong sense

of order. All spaces of different sizes try hard to avoid complete isolation in

terms of horizontal and vertical directions. The complex and interwoven beam

frame, in particular, makes the boundary surface of the space hazy and implicit,

without the least sense of rigidity and stagnation.

This example demonstrates that artisans of

Tang Dynasty architecture already had a high degree of self-conscious spatial

esthetic judgment and superb spatial handling

technique.