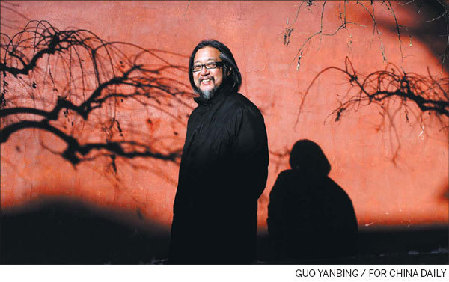

Arguably the greatest living dramatist and impresario in Chinese-language theater sees his work as a conduit between the mundane and the sublime. In what he regards as the pinnacle of his oeuvre, Stan Lai shapes ideas into a modern-day equivalent of the Bayeux Tapestry about the emotional and spiritual impact of time, Raymond Zhou reports.

Stan Lai has a clear memory of what inspired his magnum opus.

In 1990, he saw a painting in Rome by Jan Brueghel the Elder, about a huge room full of paintings. "What if a person in a story has a dream, which spawns another story, just like paintings in a painting?" he thought.

Nine years later, while touring a French castle, he noted a portrait of its owner, a French diplomat who was stationed in Italy. "What if he was assigned to China and married a Chinese lady," Lai asked himself.

Later that year, Lai chanced upon a news story about a train collision in the United Kingdom. A few weeks later, the death toll of the accident was adjusted as someone previously counted as missing and presumed dead turned out to be unscathed. He simply walked away from the scene and didn't even go back home. "What a strange act!" Lai reflected: "If I could leave like that, no matter how much debt I've incurred or how much trouble I've caused, all would be written off. Or could that be possible?"

At the end of 1999, on a pilgrimage to India he read about a young doctor in London who conducted a conversation with an old gentleman on his deathbed.

These disparate narrative strands of life experiences, direct or indirect, fell piece by piece into a mammoth and intricate jigsaw puzzle. The next year, 2000, saw the birth of A Dream Like a Dream, the most elaborate theater work, if not the lengthiest in running time, in Chinese history. It was certainly the most ambitious to date.

This 7.5-hour play, after a 2002 revival in Hong Kong and another one in 2005, again in Taiwan, is receiving the grandest treatment yet, this time in Beijing. It will be staged at the Poly Theater April 1-14 and will tour several mainland cities and then go to Singapore in the next year or two.

Stars are drawn to Stan Lai's productions. They forfeit lucrative television or film deals to participate in projects of the theater master even though this is not a new play and the method of improvisation Lai is so famous for is not employed.

On an early March day when I visited the rehearsal hall in Beijing's 798 Art Zone, there was a palpable camaraderie. The 30 actors have been rehearsing since January except for a three-week break during February. A familial environment has been established, with some of the cast bringing food and drinks and receiving ad hoc citations posted on the wall.

Stan Lai is gentle and encouraging with his actors - the opposite of an overbearing style. While he knows exactly what he wants, he does not yell at them. He calibrates their movements and blocking. But overall, he tends to focus on the total impact a setup may have on the audience. He would talk to individual actors during breaks - at some length. And he never uses the previous Taiwan and Hong Kong productions of the play as reference points.

It would be pretty hard to take a photo of Lai in a typical directorial mode, say, with a distinctive gaze or a hand gesture. He rarely does that.

Lai has noticed that mainland actors tend to over-act. "They think too much when acting and over-design their physical movements," he says. "In a sense, I have to break down what they have learned in school. But they are willing to try new things."

Lai adds local touches as actors go through scenes. During one of the Shanghai scenes, he encouraged actors to change a line into Shanghai dialect.

The principal role of a Shanghai courtesan is shared by three actresses, and not just because she has a wide range in age. The roles - should they be counted three roles - occasionally encounter each other onstage, creating a surreal moment of one person time-traveling to another era and meeting a different facet of her self. On the flip side, the same actor may also espouse several ostensibly unrelated roles, but one has to guess whether it is for logistical reasons or to hint at the possibility of reincarnation.

The Buddhist undercurrents of the play are so subtle as to be imperceptible to non-believers. But they have seeped into not only the plot, but also the structure and the staging. The opening and later transitional scenes have dozens of actors walk about the stage, clockwise, in the same direction as pilgrims would circle a Buddhist pagoda. When a person goes against the crowd, it is like a flashback in cinematic art - to go back in time.

This simple arrangement alone is at once mesmerizing and philosophical. It literally presents a milling crowd out of which vignettes and tableaux emerge - interconnected in myriad ways. Moreover, what happens onstage is not necessarily reality, some elements could be fantasy, blending into a rich texture of what was experienced and what should or could have been experienced.

The themes of life, death and love lost or gained may be universal, but the universality is distilled from era-specific and location-specific situations that are dramatized with the mastery befitting a great artist. Stan Lai is never preachy. His cosmic outlook engulfs you just like the stage on all sides. You swivel your chair and look up at these characters playing out their lives and dreams without realizing the exact moment when you turn your unique participation into a part of this process of traversing the layers of past and present, reality and fantasy, memories and regrets.

If a regular play is a solo singer, A Dream Like a Dream is like a chorus, with the listener right in the center. You don't see the maestro at a raised podium, but you'll feel his presence in every note and every whisper. That is how Stan Lai communicates his wisdom.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

By Raymond Zhou