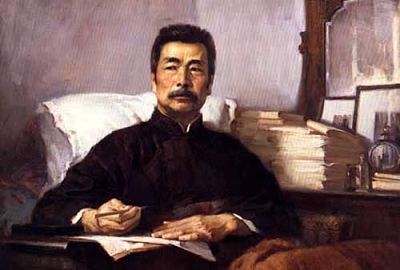

Lu Xun (1881-1936) is widely considered as China’s greatest modern writer. Although he was a prolific essayist and translator, it is for his intense and often disturbing short stories that he is best known. In criticizing repressive social norms, he aimed for nothing less than the eradication of the nation’s spiritual ills. In the decades since his death editions of his works, translations and critical studies have surged, making Lu Xun an accessible writer in most major languages. But he can also be remembered through the homes in which he lived and worked.

House museums are a type familiar throughout most of the world. They fulfill our need to pay homage to the memories of those we admire, to draw closer to them through the remnants of their worlds. The objects left behind convince us that we can have a more intimate understanding of their past owners, that we can better understand the inspirations that shaped their lives: We can marvel at how diminutive Jane Austen’s walnut table is, the better that she could work unobserved. We can wonder at the prescription of Virginia Woolf’s glasses, resting there on her desk. We can imagine Mark Twain writing in his handsome, angel-carved bed.

House museums have proliferated in China, too. Many former residences of writers, artists and thinkers have been opened to the public, some officially designated as sites of patriotic education. It is a mark of Lu Xun’s eminence as the founder of modern Chinese literature that three of his homes have been transformed into museums. And all have adjoining or nearby exhibition halls where visitors may learn about his life and his development into an unflinching advocate of literary and social transformation.

Childhood in Shaoxing

Lu Xun was born in 1881 into the once wealthy and influential Zhou family in Shaoxing, a prosperous canal town in east China’s Zhejiang Province. Lu Xun Native Place is a collection of restored buildings, including the Zhou family compound, Lu Xun’s courtyard home, the school he attended and a new museum.

Given the prominence of his family, the paucity of objects such as furniture and art works left behind is arresting and poignant – but that’s at the heart of the story. In the museum is a small patchwork jacket Zhou Zhangshou (Lu Xun was his pen name) wore as a child (as it turns out, it’s a reproduction); in his former home are a few faded items of his mother’s sewing; in the schoolroom is the desk he defaced with a carving of the character zao, meaning early. With their polished furniture, the rooms of the Native Place buildings have the appearance of comfort and well-being; however, these items are simply placeholders, not the family’s original belongings.

The Zhou family suffered a series of misfortunes that marred Lu Xun’s childhood. His grandfather, a member of the Qing Dynasty Imperial Academy, was imprisoned for attempting to bribe an imperial examiner. His father was unable to find work and descended into alcohol and later chronic illness. Much later, in writings about his Shaoxing childhood Lu Xun recalled his dreary relay between pawnshop and pharmacy to trade his mother’s jewelry, their clothes, furniture and trinkets to pay for ever more fantastical medicines for his father: sugar cane that had survived three years of frost, chaste crickets, worn leather of broken-down drums. None of these could save him – he died at 35, and the teenaged Lu Xun was never to forget the deprivations and humiliations of those years.

Lu Xun’s memories of Shaoxing remained conflicted – he was nostalgic for childhood pleasures and the richness of South China literary culture, but in both fictions and autobiographical essays, he was deeply critical of the inhumanity he first encountered there.

Yet, the atmosphere now at Shaoxing is almost unfailingly celebratory, and evocative of the unclouded days when Lu Xun was known as “lamb’s tail” for his liveliness. The Native Place buildings display the elegant monochromes of a traditional South China canal town, reflected in the water that is so much a presence in this Yangtze Delta region. The pawnshop is an after-thought, far overshadowed by the neatly tended Hundred Plants Garden where Lu Xun foraged as a small boy for wild raspberries, trapped crickets and jumped clear of the noxious spray of tormented stink bugs. In a side courtyard a visitor can sip warm rice wine spiced with ginger and enjoy the sight of hibiscus sprawling rampantly against a garden wall, as the Zhou family must once have done before they had to sell their possessions and, finally, their home.

We recommend: